Farmers in Maharashtra and Rajasthan Turn to Robotic Cleaning to Improve Solar Output

Dust-heavy feeder-level projects push automation in solar O&M

January 14, 2026

Follow Mercom India on WhatsApp for exclusive updates on clean energy news and insights

The rapid rollout of the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) program is gradually transforming India’s rural solar landscape by enabling decentralized, feeder-level solar power projects for agricultural use.

The solarization of agricultural pumps in states such as Maharashtra and Rajasthan has also led to the increasing use of robotic module cleaning systems under PM-KUSUM and state-linked programs such as Maharashtra’s Mukhyamantri Saur Krushi Vahini Yojana (MSKVY).

Generation efficiency issues

While the program has improved daytime power availability for agriculture, developers and operators are increasingly grappling with operational challenges that directly affect project performance.

Among the various operational issues, dust accumulation on solar modules has emerged as one of the most significant and underestimated threats to generation efficiency.

Most KUSUM solar projects are located in agricultural belts, semi-arid zones, and dry regions, often surrounded by unpaved roads, active farming operations, and loose soil. These site conditions make dust accumulation on solar modules unavoidable.

Robotic cleaning, once considered suitable mainly for large utility-scale solar parks, is now finding relevance in feeder-level and distributed solar assets, not as a futuristic add-on, but as a practical operations and maintenance (O&M) support that could determine long-term viability.

Robotic solar cleaning is viable only for Component A and Component C (feeder-level) projects, as they involve large, contiguous, ground-mounted solar projects with uniform panel layouts and centralized operations. Component B or Component C (individual pump solarization) is not viable due to their small, dispersed system sizes.

According to industry experts, robotic cleaning of solar modules is six times more cost-effective than traditional methods.

Dust Accumulation

KUSUM solar projects are typically located in agricultural belts, dry zones, and semi-arid regions, often surrounded by unpaved roads and active farming activity. These conditions make dust accumulation inevitable.

According to Kushal Shah, Managing Director at B. U. Bhandari Energy, generation losses of 5% to 7% are common under normal dusty conditions, but during peak summer and dry seasons, the losses can be as high as 10% to 12% if cleaning is not regular.

He adds that the Maharashtra government’s structured implementation under MSKVY, combined with central support, has accelerated solar deployment and consequentially the need for robust O&M strategies.

In Rajasthan, where arid conditions prevail, the impact of dust is even more pronounced. Developers working on KUSUM feeder projects report that soiling losses can reach 15% to 20%, which directly threatens project performance.

Manual Cleaning Unsustainable

Traditionally, manual wet cleaning has been the dominant solution. Wet cleaning is effective in removing stubborn deposits like bird droppings, which can otherwise cause hot spots and long-term module damage.

Manual cleaning typically costs ₹1 (~$0.011) to ₹1.2 (~$0.013) per panel and requires 7–12 tons of water per MW for each cycle. In remote districts, labor availability is erratic, with cleaning cycles often stretching to 30 to 45 days. Between cleaning cycles, performance drops sharply, often by 15% to 20%.

Rajasthan’s Numbers Make the Case

For developers operating in Rajasthan and Gujarat, the economics of dust-related losses are becoming impossible to ignore.

Keyur Gajera, Director at Earthwave Group and Veda Solar, notes that field data from KUSUM sites shows panels losing around 0.37% efficiency per day due to dust accumulation.

“That doesn’t sound like much until you see it compound. In summer months, we’re talking about 15% to 30% generation loss,” he says. For a 1 MW plant selling power at ₹3.14 (~$0.037)/kWh, this translates to an annual revenue loss of ₹1.2 million (~$13,200) to ₹1.5 million (~$16,500).

Robotic module-cleaning systems are emerging as a practical solution given these constraints.

Their key advantage lies in frequency. Unlike manual cleaning, which depends on labor and water availability, robots can clean daily or on alternate days, preventing dust from building up to damaging levels.

Shah points out that, when deployed correctly, robotic systems can recover up to 90% to 95% of soiling-related generation loss. “Consistent, water-free cleaning ensures stable output across seasons and reduces long-term performance degradation,” he says.

From a cost perspective, robotic cleaning typically costs about ₹0.20 (~$0.0022) per panel, compared to ₹1 (~$0.011) to ₹1.2 (~$0.013) per panel for manual cleaning. Over time, this difference becomes significant, especially in dusty regions where cleaning accounts for a large share of O&M expenses.

Operational Realities

Despite growing adoption, the picture is not uniformly positive. Kayan Kalthia, Director–Business Development at Kosol Energie, highlights that in feeder-level KUSUM projects, robotic performance depends heavily on operational discipline.

“In arid regions, robotic cleaning helps limit further dust accumulation, but timing is critical,” Kalthia explains. “If robots operate during early mornings or evenings when dew is present, dust sticks more strongly to the module surface, reducing effectiveness.”

KUSUM Program Framework

The program entails central financial assistance (CFA) of ₹344.22 billion (~$3.8 billion), with the feeder-level solarization projects eligible for a CFA of up to 30% of the installation costs, capped at ₹10.5 million (~$116,488)/MW.

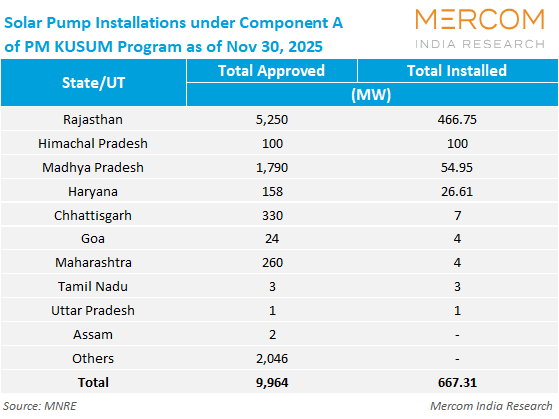

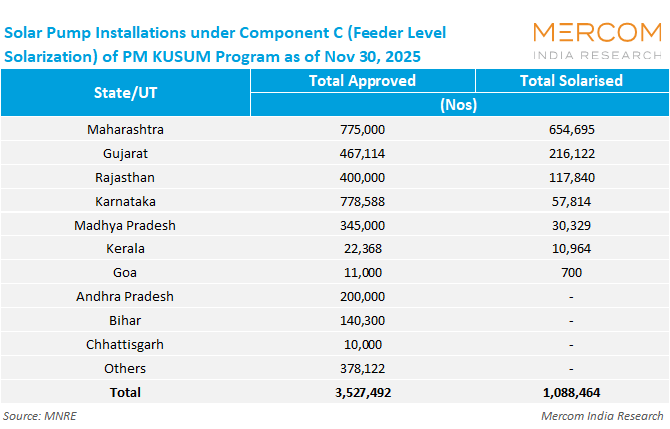

The PM-KUSUM program comprises three components: the installation of small-scale solar power projects (Component A), the deployment of standalone solar-powered pumps (Component B), and the solarization of existing grid-connected pumps and feeder level solarization1 (Component C).

Component A enables the setup of decentralized, ground-mounted solar power plants ranging from 500 kW to 2 MW, developed by farmers, farmer producer organizations, panchayats, or developers on fallow, barren, or cultivable land, with the entire power generated sold to distribution companies.

Component C (feeder level solarization) focuses on solarizing entire agricultural feeders by connecting them to a centralized solar plant of around 5 MW to 20 MW, ensuring daytime power for multiple irrigation pumps while exporting surplus energy to the grid.

As of November 2025, more than 1 million feeder-level solar power projects have been solarized under the PM-KUSUM program, with Maharashtra accounting for 654,695 installations and Rajasthan 117,840 installations.

While both components involve utility-scale ground-mounted solar plants, Component A is aimed at decentralized power generation and farmer income diversification, whereas the feeder level is designed to reduce DISCOM subsidy burden and improve reliability of agricultural power supply.

O&M Economics Under KUSUM

KUSUM feeder-level projects typically incur annual O&M costs of 1.2% to 2% of the total project cost, with module cleaning alone accounting for 30% to 40% of the total in dust-prone regions. Robotic cleaning is increasingly being evaluated to stabilize these costs over the 25-year project life.

While the upfront investment of ₹800,000 (~$8,800)/MW to ₹1.5 million (~$16,500)/MW may seem steep, developers note that it accounts for only 2% to 3% of the total project cost. Over the long term, robotic cleaning can reduce overall O&M expenditure by approximately 20% and improve annual energy yield by approximately 5%.

However, robots do not eliminate the need for site visits. Supervision, brush replacement, troubleshooting, and periodic thermal inspections are essential. In some cases, site visits may even increase due to preventive monitoring requirements.

Small Projects, Big Constraints

One of the biggest hurdles in Maharashtra and Rajasthan is integrating robotic systems into smaller KUSUM projects ranging from 500 kW to 2 MW. Irregular land parcels, short table lengths, uneven terrain, and limited auxiliary power complicate deployment and increase the need for manual intervention.

Kalthia notes that robotic systems are most cost-effective for long, continuous module tables, a condition many feeder-level projects lack. While new modular and battery-operated robots are addressing some of these challenges, land configuration remains a decisive factor.

Despite limitations, the direction of robotic cleaning is clear. Rising labor costs, worsening water scarcity, and the need to meet long-term capital utilization factors and performance guarantees are pushing KUSUM developers towards automation.

Gajera believes that within five years, most KUSUM projects above 1 MW in dusty regions like Rajasthan will adopt robotic cleaning as a standard O&M feature.

“For us, this isn’t about fancy technology,” he says. “It’s about ensuring consistent generation for 25 years and keeping farmers’ power reliable.”

In this sense, KUSUM projects, particularly in Maharashtra and Rajasthan, are doing more than expanding rural solar capacity.